By Richard G. Biever

On a clear night, Jim Tague can see forever.

Through his backyard telescope, he can look out across the eons. What he finds there among the ancient dapples of starlight and emptiness, he’s sometimes not sure of. But that’s what’s kept him stargazing since he was a boy.

“What draws me to it is that mystery. It’s a big universe to wonder about,” he said.

Most nights are routine. He almost takes for granted the galaxies and star clusters he’s visited so often. But sometimes, even this 76-year-old retired banker, a Kosciusko REMC member from Winona Lake, is struck by the magnitude of it all. “There are times you’ll think, ‘My word, I’m looking across 2 million light years of space.’ Sometimes it just dawns on you.”

On a clear night, Zolt Levay attaches his digital camera to a tripod planted firmly on terra firma and opens the shutter.

During the day, the vastness of the universe is lost in the sun; everything is awash with light. But at night, that curtain is lifted. Levay captures awe-inspiring images of what’s really out there beyond the veil.

Levay said it’s the curiosity and mystery of the night sky that intrigues him as the heaven and the Earth come together in his images. “The sky is so different from our experience of the terrestrial environment,” he said.

His photos of the spangled trail of the 13.5 billion-year-old Milky Way against earthly well-worn and weathered barns and covered bridges offer a whole new meaning of grandeur and the concept of age.

“Our personal experience on the Earth is this tiny little place. Even just looking at the night sky gives you a glimpse of that,” he said. “As you begin to study the universe and learn, and you begin to understand what you’re looking at, it makes the universe larger, in a sense. It gives this three-dimensionality to the universe that it otherwise doesn’t really have.”

On clear nights, all across rural Indiana, far from the glare of city lights, astronomers like Levay and Tague turn the lenses of their cameras and telescopes of all sizes and shapes into the swirling starry skies.

Some of these starfaring voyagers are fascinated by the simple sights of the night sky, the well-traveled constellations and planets. Others like the physical challenge of tracking down obscure astronomical objects to see what relatively few others have seen. Still others are looking for things no one has ever seen.

Some simply enjoy the camaraderie in the astronomical clubs or “societies” around the state that devote an evening or two a month to these heavenly pursuits.

About a dozen astronomical societies are scattered across the state and on the borders. Their memberships range in size from a dozen astronomers to 240. Members vary from newcomers and casual observers to hard-core amateurs who intensely delve into research. Membership fees are generally around $25-$30 per year and may include a subscription to national monthly publications and usually a club newsletter.

John Molt is president of the Indiana Astronomical Society, which includes members from central Indiana and is the state’s largest group. He said they count 40-50 regularly active members who attend meetings and events.

Of course, “regularly” in this year of COVID-19 has taken different meanings. Most all the planned public gatherings Indiana’s astronomical societies usually hold throughout the year had to be canceled. Members still met privately in small groups to gaze into the night skies, especially when Comet NEOWISE showed up for a brief couple of weeks in the morning, then evening skies as it looped its way around the sun this summer. (If you missed it, the 3-mile wide ice ball isn’t expected to be back again for another 6,800 years.)

Molt, 65, is a certified arborist and said he’s interested in all things outdoors. “I just like looking at the interesting things in the sky. I don’t think too much how they got there, how long they will be there. I just enjoy the visual part of seeing them.”

Levay is also a member of IAS. He moved to Bloomington with his wife, a native Hoosier, after he retired a few years ago from the Space Telescope Science Institute that operates the Hubble Space Telescope. The 68-year-old Levay, who has a degree in astronomy from Indiana University, worked on the Hubble Space Telescope for 35 years in the institute’s outreach office in Baltimore. His job was to take the data Hubble gathered to produce those incredible photographs and graphic illustrations the public saw from Hubble.

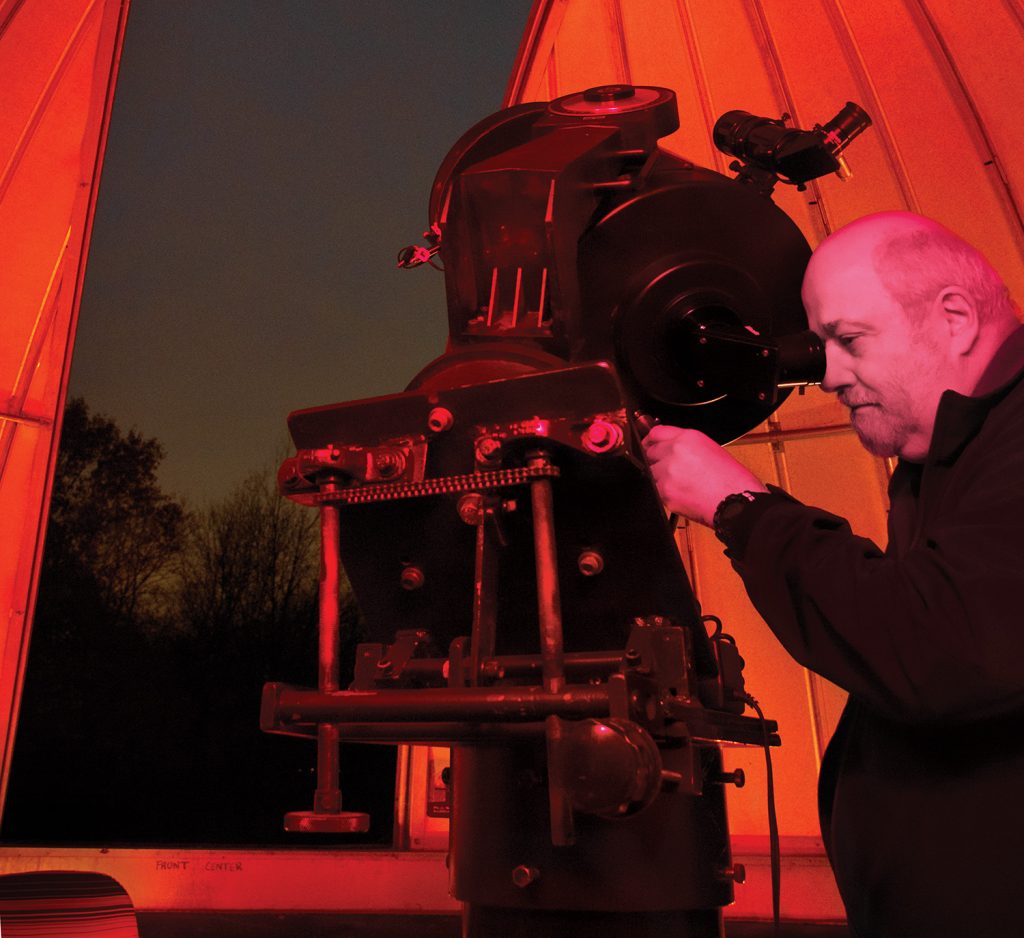

Kurt Eberhardt, 63, a Kosciusko REMC member and long-time president of the Warsaw group, had intended on making astronomy his livelihood when he went to Indiana University in the mid-1970s. But the space program was beginning to wane and the few jobs available were becoming even more scarce. He was advised to go into astrophysics.

But Eberhardt didn’t want to be stuck inside. “I’d rather be out under the telescope,” he said, than pushing a pencil with numbers and readings.

He then studied geology and eventually became a high school science teacher. Though retired from teaching, he still combines his interests in astronomy and geology by studying meteorites.

He said members of the groups all bring different backgrounds and interests to astronomy. And when they get together at McDonald’s after a meeting, conversations can be probing and lively — from various astronomical topics to the origins of man and theology to Star Trek.

Molt and Eberhardt both noted the groups thrive on the diverse interests that members bring. Some members, like Levay, excel at photography. Others love the public outreach and speaking to school groups. Still others just enjoy the simplicity of learning the night sky and being able to point out the constellations.

“There are bunch of different ways to approach the hobby,” Eberhardt said. “You find all these other people who share a common language and interest, but they all approach it from a different way. Areas that you may not have thought of before, you watch another guy doing it, so you learn about all kinds of stuff.”

Group members speak at libraries and schools and host public “star parties” throughout the year where folks can come out to learn and observe the skies through a number of telescopes.

Many of these societies have built their own observatories through fundraisers and donations that they open to the public. Others have access to public observatories.

The Indiana Astronomical Society has use of Indiana University’s historic Link Observatory. Amateur astronomer and noted Indianapolis surgeon Dr. Goethe Link built the observatory and equipped it with a 36-inch reflector telescope, the largest in Indiana at the time, for his own personal use in the 1930s. In 1948, Link donated it to IU with an endowment and stipulation that it be used to generate interest in astronomy with the general public. The telescope is still the second largest in Indiana, behind Butler University’s Holcomb Observatory.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, the observatory, situated atop a wooded ridge south of Mooresville, was the site of many asteroid discoveries. But by the early-1980s, the observatory had become obsolete for IU’s research purposes. In 1986, IU handed the key to the observatory to the amateur society. Before the pandemic, the observatory was regularly open on clear weekend nights to the public.

Steve Haines, the event and outreach coordinator for IAS, said his interest in astronomy is creating interest for others by showing them the sights. “One of the things you will never forget in your life is the first time you see Saturn through a telescope,” he said.

But seeing isn’t always believing, Tague and Eberhardt discovered. The Warsaw group’s observatory is on a hilltop inside Camp Crosley YMCA near North Webster. Often on clear nights during special camp sessions, group members open up the roof for the campers and their parents to gaze through their larger telescope. When groups from Chicago had come, Tague said they would show them Saturn and its rings. “I don’t know how many times this happened, but they would actually look around to see if we didn’t have a picture of that thing hanging there. They couldn’t believe what they were seeing.”

Eberhardt said one guy was so incredulous, he came up after everyone else had left and said, “Be honest with me, you’re showing us a picture, right?”

“No, we’re showing the real thing,” Eberhardt told him. To convince the man, Eberhardt turned a second telescope outside toward Saturn and let him look again. “You wouldn’t happen to have two pictures would you?” the man asked … “Am I REALLY seeing it?”

Eberhardt noted that’s one of the neat things about astronomy: Many of the most popular objects are there for all to see in real time, and one never tires of seeing them. Some are a little more challenging and take some skill to find.

Astronomy is one science that is accessible to everyone in the most basic sense, noted Levay. “Everybody sees the moon, and everybody sees the same moon all over the Earth. Everybody can experience it. The average person has no real world experience with a lot of areas of science, such as nuclear physics, but with astronomy you have that real-world connection of being able to see the night sky.”

Haines noted young students always have interesting comments as they try to relate what they know about space, such as asking if astronomy club members are “astronauts.”

They may not be astronauts, but when you look at distant stars, you are space voyagers — and time travelers. “People always talk about telescopes as being time machines,” said Levay. “And that’s another aspect of studying the sky and studying astronomy that’s attractive to a lot of people. The farther we look, the farther we’re actually looking back in time, as well, because light takes time to travel to us. So, we’re really seeing things as they were thousands, or millions, or even billions of years ago.”

On a clear night, the rural sky reveals heavenly highways and hamlets, byways and burgs to travel upon and visit. Astronomers and stargazers leave this tiny tired and torn old world to both wander and wonder about all that’s above: whether it means looking through a large telescope or simply gazing upward from a grassy hillside; whether it means discovering a variable star or wishing on the first star seen tonight.

Some look to the clear night sky for answers to questions asked since the dawn of time: How did we get here? Where do we fit in the grand scheme of it all? Where are we going?

Some astronomers find tiny specks of answers in telescopes, collected data, computations and calculations. Some find a deeper faith in God amid the mysteries and incomprehensible vastness.

And if the clear night sky causes us just to stop to ponder these things for even a moment, … then maybe that’s just what a clear night is for.

RICHARD G. BIEVER is senior editor of Indiana Connection. This story is an updated account of one he wrote for this publication 25 years ago.

Sky shows coming our way

For hearty souls willing to bear the nighttime chill, the heavens will produce some extraordinary sights this month and next if the sky is clear:

Dec. 13-14

Geminids Meteor Shower. Considered by many to be the best meteor shower, the Geminids will produce up to 120 multicolored meteors per hour during this peak time. The shower runs annually Dec. 7-17. The nearly new moon will ensure a dark sky. Meteors will radiate from the constellation Gemini, but can appear anywhere in the sky.

Dec. 21

Great Conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn. This coming together happens every 20 years, but this will be the closest they’ve appeared since 1623. The two bright planets will appear like a bright double planet. Look to the west just after sunset.

Dec. 21-22

Ursids Meteor Shower. The Ursids is a minor meteor shower producing about 5-10 meteors per hour at its peak. The shower runs annually Dec. 17-25. Meteors will radiate from the constellation Ursa Minor, better known as the Little Dipper, in the northern sky, but can appear anywhere in the sky.

Jan. 2-3

Quadrantids Meteor Shower. The Quadrantids is an above average shower, with up to 40 meteors per hour at its peak. The shower runs annually from Jan. 1-5. Meteors will radiate from the constellation Bootes, but can appear anywhere in the sky.

Star Tubin’

Instructors have long sought new ways to liven up their lecture classes. But Ivy Tech Community College associate professor Kurt Messick has boldly gone where no prof has gone before.

For his summer and fall astronomy classes, made virtual by COVID-19, the Bloomington instructor has tapped a well of guest speakers that reads like “Star Trek” cast reunions and a who’s who of science fiction and pop culture phenoms. And his students are loving the cameos and their quips.

Some 45 stars have contributed the mostly short, 1-3 minute, unscripted videos. Messick usually injects them during announcements, special emails, introductions to lectures, or discussion-board pieces. He said he gathered them after “carpet bombing” Hollywood with requests during quarantine downtime, initially only expecting a few stars to respond.

William Shatner, Capt. James T. Kirk of the original “Star Trek” crew, told the Bloomington Ivy Tech students that their minds, like the Starship Enterprise, were on a “voyage of discovery.” “You push the boundaries of what we know very quickly,” the affable actor said.

Messick plans to plug the clips in as long as classes remain virtual, and even beyond. But you don’t need to enroll to see them. Messick has posted them on YouTube at https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC_5KBOvR-da9h_xgOVIlfzQ.

Don’t give the ‘closet telescope’ for Christmas

If you’re new to astronomy and thinking of gazing upon a Christmas star through a new telescope, Indiana’s astronomical societies have some advice: wait — and first join a nearby astronomical society, or at least attend a society meeting or public event (which may be virtually until COVID concerns pass).

Folks that do, Haines noted, especially those who purchase inexpensive telescopes on a tripod from department stores, will often be dissatisfied because the instrument won’t perform as advertised or as the recipient might expect. And soon, the common fate is the instrument is relegated to a closet.

Many members of astronomical societies love sharing their interest with newcomers and will help you pick the right instrument based on your interests — what you hope to see in the night sky and learn, how mobile you want the scope to be, and how much you can afford. In addition, members of astronomical clubs are always upgrading their equipment, too, which means well-maintained, used scopes are often on sale to fellow club members for a fair price.

Finally, a good pair of binoculars often will satisfy a newcomer — plus binoculars have the added practicality of mobility and can be used in watching sports or observing wildlife. When Comet NEOWISE appeared low in the evening sky this past summer, binoculars were sufficient in seeing the fuzzy-tailed snowball against the haze on the horizon.

For more information

To find an astronomy club near you, here’s a link to a list of 14 clubs around Indiana: https://www.go-astronomy.com/astro-clubs-state.php?State=IN.