By Richard G. Biever

Danielle Long asked artist Bill Wolfe to hold her 1-year-old son as she stepped onto a riser in Wolfe’s studio. Then, she peered deep and long into the eyes and face of the sculpture Wolfe had conjured from clay. It was the face of her late husband, fallen Terre Haute police officer Brent Long.

“You know?” she said turning to Wolfe, still holding the couple’s little boy. “It’s almost like he’s still alive.”

For Wolfe, entrusted to preserve the likeness of the slain officer for a memorial, it was a powerful moment. “You’re like, ‘Wow.’ It’s really emotional. Just no words can describe that feeling, and, of course, my eyes welled up.”

For 20 years, Wolfe has been pressing life and soul into clay sculptures. He’s gaining a reputation for the realism he brings to life-sized and larger-than-life monuments and memorials of heroes lost and Hoosier legends that are then cast in bronze.

Among the most visible works the West Terre Haute artist has created:

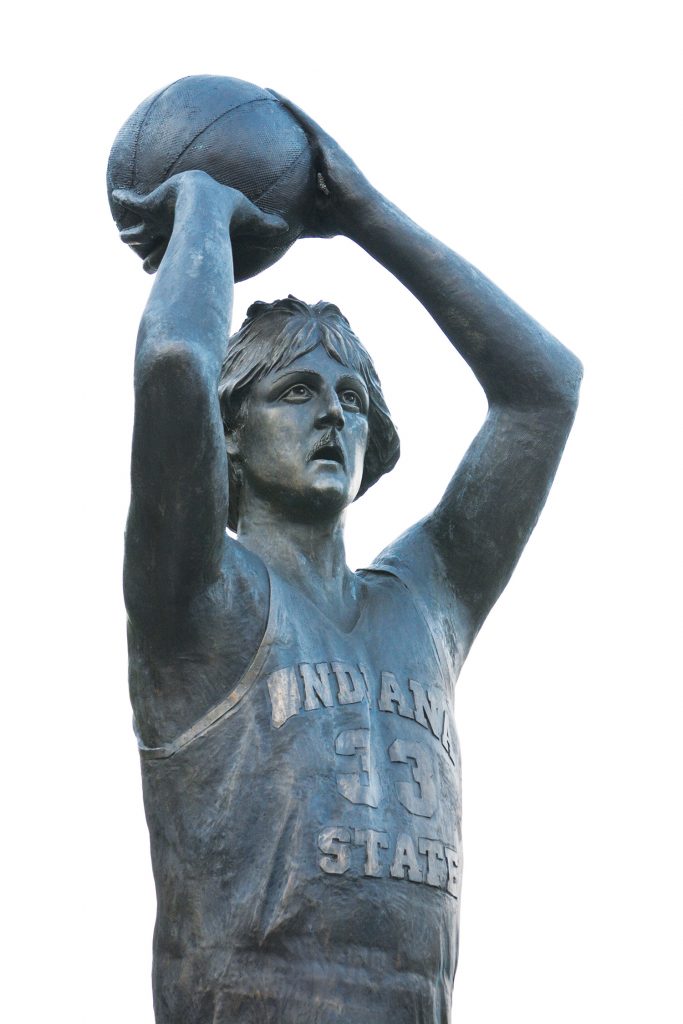

- The 15-foot Larry Bird, in his Indiana State University basketball uniform, taking a jump shot in front of ISU’s Hulman Center.

- Indiana aviation pioneer and World War I flying ace Weir Cook greeting travelers entering the Indianapolis International Airport terminal named for him.

- Muncie’s tribute to Hurley Goodall, a retired firefighter and a long-time leader in the community and the state’s black legislative caucus; poet James Whitcomb Riley hanging out in front of his boyhood home in Greenfield; and French-Canadian explorer and military leader François-Marie Bissot, Sieur de Vincennes, surveying the Wabash River along the riverwalk in Vincennes.

- American servicemen and women for various community memorials and monuments in Terre Haute, Avon and Carmel.

And sadly, he’s now enshrined forever in bronze two Terre Haute police officers from the past decade: Long, who died 10 years ago this month, and Rob Pitts in 2018.

“The most emotional ones,” the 66-year-old artist said, “are here in Terre Haute. We’ve had two officers killed in the line of duty. We’re getting ready to put both of those statues together on a memorial plaza in front of the new police station.”

Wolfe guesses he’s done around 20 statues, some larger than others.

The process

He starts with lots of photos of his subjects — if available. “Getting a good likeness is probably the hardest part. But if you have plenty of pictures to work from, that’s a godsend,” he said. Since he hadn’t met Larry Bird before Bird’s statue’s dedication, he used photos of the French Lick phenom in action from all angles.

Wolfe usually starts with the head, shaping the clay. Lately, he noted, he’s been cutting the basic forms of the statues from foam. Then he applies a layer of clay over the foam in which he sculpts the details. “Once my clay is completed and the client looks at it and gives approval, then I take it to the foundry.”

There, a wax mold is created of the clay sculpture and cut into sections. From the wax, a bronze casting is made. The bronze sections are then welded together and the seams are smoothed out. Finally, the bronze is heated and a chemical combination called “liver of sulfur” is applied to give it a dark patina.

If the subject is still living, Wolfe might ask to do something he admits sounds “really weird” before starting. He’ll ask if he can run his hands over and around the subject’s head. “I can gather as much information that way as just looking at them because a lot of sculpting is just feel … touching.”

With Goodall’s statue a few years ago, he asked Goodall, who is now 94, if he could touch his head and got the OK. “He let me just kind of feel his brow and his forehead and all around the bulk of his head. And I truly got a lot from that.”

With his latest completed and installed work of Vincennes, he had no references to work from. “There are no pictures of Vincennes in 1730 to 1750.”

Wolfe created his own portrait of the man in his mind. “I pretty much started on the head again. I work late hours, two o’clock in the morning. I just looked at this egg shape that I carved out of foam, and then I kind of channeled François. I said ‘OK, Mr. Vincennes, tell me what you look like.’ So, I just started sculpting, just applying the clay. Now, some people told me I made him look like me. If I did, it wasn’t intentional.”

Remembering ‘Slick’ Leonard

One missed opportunity Wolfe said he regrets came in April with the death of Indiana basketball legend Bobby “Slick” Leonard at age 88. Leonard hit the winning free-throw for the 1953 Indiana University NCAA basketball championship team and also coached the Indiana Pacers to three ABA championships. He then became the enthusiastic “Boom Baby” voice of the Pacers. Wolfe wanted to make photos and prepare a statue of him. “Terre Haute should have something made because this was his hometown.”

Wolfe got Leonard’s phone number, but then, “I kind of chickened out because I didn’t want him to get that feeling that ‘Bill Wolfe is contacting you before you die.’ When I heard that he passed … I said I should have just went for it.”

Wolfe still recalls when the Bird statue was unveiled at ISU; he politely shook the hand of Bird and basketball legends Quinn Buckner and Bill Walton who were on the stage with him, but his biggest thrill was down the line with Leonard. “When I shook Slick Leonard’s hand, he looked at me and said, ‘Bill, we’re so proud of what you’ve done for Larry. And I just want to thank you.’

“It gave me goosebumps,” Wolfe added. “I almost started crying.”

Wolfe said all the memories as a kid looking up to Leonard as the Pacers coach came back. “How much better can that get for an artist: to be able to do that and meet Larry Bird and Slick Leonard?”

Keeping memories alive

Though he’s now beyond “retirement age,” Wolfe said another great thing about being an artist is there is no retirement age. But he does look back.

“In my life I’ve been lucky to have a profession that is something that I love to do. And in that profession, I’m giving respect and honor to people who have done great things with their lives.”

While some figures he’s sculpted, like Orville Wright and Larry Bird, would have always lived on, others, like the fallen local police officers might not. “It keeps their memory alive,” Wolfe added of his works. “If you didn’t have [the statues], they would gradually fade away over the years. It keeps their names in the lights.”

Bronze casts should last a thousand years, Wolfe noted. Long after all who are alive today have turned to dust and clay, the tributes Wolfe’s hands once pressed into clay will live on and on.

RICHARD G. BIEVER is senior editor of Indiana Connection