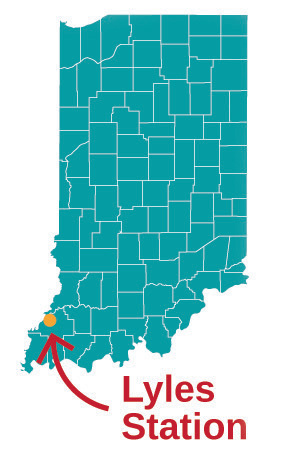

While Indiana native Alonzo Fields was making a home for himself as chief butler and maître d’ at the White House, Lyles Station, the historic Black community where he was born in 1900, was being lost to the shifting tides of fortune and fate.

In 2016, that almost forgotten community also found a home in Washington — with the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture opening near the Washington Monument.

“Lyles Station offers a window into the largely unknown story of free black pioneers on the American frontier,” the Smithsonian notes of its permanent exhibit. “African American farmers have been cultivating their own land in and near the area since 1815. Through two centuries of tumultuous change, the community of Lyles Station has rested on the pillars of home, farm, church, and school — and on an unbroken history of land ownership.”

Folks needn’t travel to Washington to learn about Lyles Station. Though much diminished from its heyday when Fields was born, Lyles Station is still home to families of farmers, nearly all descended from the original settlers, who still work the land. And, the community’s story is being told at the restored Lyles Station Historic School & Museum, one of the community’s last remaining landmarks.

BOOM, THEN DECLINE

The school was built in 1919 and produced many high-achieving graduates. It closed in 1958. By 1997, the school was collapsing in ruins when the Lyles Station Historic Preservation Corporation formed and teamed with Indiana Landmarks to rescue the building.

“In Washington, D.C., they’re looking at southwestern Indiana as having a unique place that is still farming. And they want to tell that story,” said Stanley Madison, chairman of the preservation corporation and volunteer director of the museum. “We have deep roots.”

Those deep roots were planted by free Black families attracted to the area by its fertile land, created by the nearby Patoka, White and Wabash rivers. The settlement, later called Lyles Station, grew into a robust self-sustaining farming community of approximately 800 residents. At its peak, from 1880 to 1913, Lyles Station consisted of 55 homes, a post office, a rail station, an elementary school, two churches, two general stores, and a lumber mill.

The rivers that helped the community grow and thrive were also prone to flooding. After a devastating flood in 1913 that destroyed much of the town, Lyles Station began a steady decline. Madison noted many younger members of the community left for new opportunities and good-paying jobs with developing industries in places like Gary, Indianapolis, Evansville and Ohio, leaving only core family farmers behind.

LYLES STATION HISTORIC SCHOOL AND MUSEUM

953 N. 500 W. | PRINCETON, IN 47670

For more information about the museum and its various programs available to educators and schools, contact the museum at 812-385-2534, lylesstation.com, and on Facebook.

Museum Hours: Tues.–Sat., 1–4 p.m. (Central Time)