Blame it on a Q-29, a safety device the size of a shoe box, at a remote Canadian electrical substation near Niagara Falls. Blame it on human error for setting the suspect Q-29’s limit too low for the transmission line it protected. Or blame it on the hubris of those who never fathomed so small an error could cascade into such a cultural benchmark of failure.

No matter who or what was to blame: When power use rose along the eastern Great Lakes at dusk that crisp November day 50 years ago, that small safety device prematurely tripped, as it was mistakenly set to do, and shut down its transmission line. The Great Northeast Blackout of 1965 — a power failure the likes of which the world had never seen — had begun.

No matter who or what was to blame: When power use rose along the eastern Great Lakes at dusk that crisp November day 50 years ago, that small safety device prematurely tripped, as it was mistakenly set to do, and shut down its transmission line. The Great Northeast Blackout of 1965 — a power failure the likes of which the world had never seen — had begun.

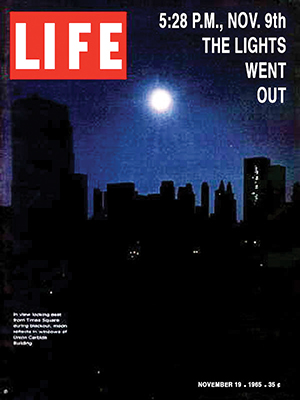

Like dominoes, equipment down the interconnected lines overloaded. The failures rippled — then cascaded out. Within minutes, most all of New York state and parts of seven neighboring states and Canada, including New York City, Boston and Toronto, were left in the dark. Manhattan’s glittering skyscrapers became black hulking monoliths against a full moonlit sky. Almost everything electrical shut down over 80,000 square miles. It was “The Twilight Zone” in real life.

Some 800,000 people in New York City had to walk from stalled subway trains in the dark tunnels while others were trapped in elevators and had to be rescued. Stranded commuters filled every available darkened hotel room or slept in lobbies.

The Nov. 9, 1965, blackout affected some 30 million people and lasted up to 13 hours. Not until the August 2003 blackout in much the same area did North America see another blackout that compared.

A freighter glows in a Brooklyn harbor while Manhattan’s skyline is shrouded in darkness during the November 1965 blackout. Some small pockets of New York City kept power during the massive 13-hour blackout, and, in some towns around the Northeast, quick-acting utility operators, monitoring their system, threw switches to disconnect their utilities from the grid before they were caught in the cascading failure.

World Telegram & Sun photo by Stanley Wolfson/Library of Congress

“Where were you when the lights went out?” became a catch phrase for the decade and even the title of a big-screen Doris Day comedy about crazy events set in motion that night. The blackout was joked about in popular TV shows of the day like “Green Acres” and “Bewitched.” (Please see sidebar on pop culture.)

But to utilities and policy makers on both sides of the Great Lakes, the blackout was no laughing matter. It exposed issues in the humongous North American electrical highway called “the grid,” the largest machine mankind ever built, that interconnects power generators, power lines and the end-use electric consumers.

“That was the first blackout of that scale in the United States and really got the attention of our government,” said Barry Lawson, associate director of power delivery and reliability with the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association. “It was a significant wake up call for everybody.”

Soon after, Congress demanded improvements. Utilities that generated and transmitted electricity came together to create a voluntary organization — the National Electric Reliability Council — to establish standards and policies and provide peer oversight. “It put into place a lot of practices and policies that the industry agreed to do,” Lawson said.

Since then, innovations in technology have allowed for better gathering of data and monitoring of the flow of power across the grid. But at the same time, changing laws and regulations fundamentally shifted the way the grid and utilities operate. A whole new set of challenges has arisen — affecting the largest power producers down to the smallest distribution cooperatives.

“There are a lot of things that can impact the grid still in front of us,” noted Lawson.

North America’s electric grid may be the largest interconnected machine on earth and truly a marvel of engineering, but it wasn’t initially designed that way. It was created as needed — over the course of 100 years — one section at a time.

The traditional utility model that grew with the use of electricity in the early 20th century was vertically integrated. That is: Within a given service territory, one utility owned and operated the power plants and the transmission and distribution power lines to meet the needs of the consumers in that territory.

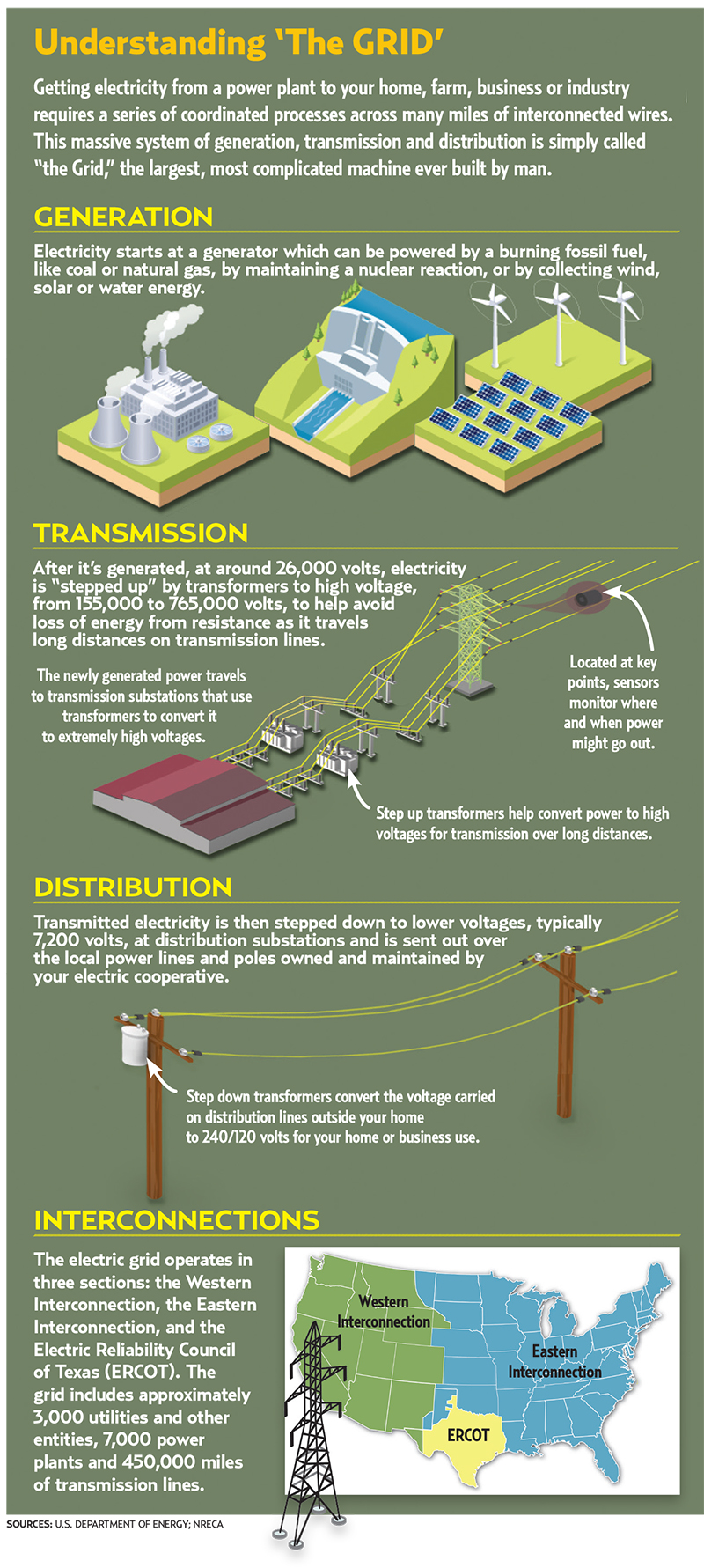

Over time, utilities connected with neighbors for mutual benefits — like backup power when needed. The networks grew. Today’s grid includes approximately 3,000 utilities and other entities operating 10,000 power plants sending energy across 450,000 miles of transmission lines.

There are actually three power grids in the 48 contiguous states: the Eastern Interconnection (generally for states east of the Rocky Mountains); the Western Interconnection (for states from the Rockies to the Pacific Ocean); and the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (which covers approximately 85 percent of Texas). The three grids operate as islands, independent of each other for the most part. The Rockies make for a logical, logistical geographic split, and Texas stands apart partly because of its “Lone Star” traditions of geographic, political and economic independence.

The power grid envisioned in the 1900s was not built for today’s population and the profusion of electrical devices that now permeate our lives. The grid is now stretched to capacity.

Girding of the grid

After NERC came along in 1968, overall reliability improved for 30 years. “It worked well in the vertically-integrated industry-owned transmission model,” said Lawson.

Congress tossed the monkey wrench of unintended consequences into the already complicated grid works in 1992 when it deregulated the generation of electricity. The “vertical” began to break down as competitive independent generators with no transmission operations or load-serving obligations entered the wholesale marketplace. Owners of existing transmission lines were required by law to allow open access to the network.

By the late 1990s, with all comers allowed to enter the fray, voluntary compliance with NERC standards and policies became inconsistent. New reliability problems began showing with outages in the Western grid. Lawmakers and utility industry folks talked about establishing additional oversight.

“It was not clear if this voluntary regulatory group using peer pressure would be able to continue to ensure the high level of grid reliability that the utility industry provided,” Lawson said.

That answer became clearer Aug. 14, 2003.

During that hot afternoon when power use was high, a series of malfunctions, mishaps and mistakes escalated into the worst blackout in North American history.

During that hot afternoon when power use was high, a series of malfunctions, mishaps and mistakes escalated into the worst blackout in North American history.

It started when heavily loaded transmission lines sagged into overgrown trees in Northern Ohio, causing those lines to fail. Alarms to warn operators of the growing malaise malfunctioned, and the severity of the situation went unrecognized until it was too late. Just as in 1965, a blackout cascaded across the Northeast. Some 300 transmission lines failed. Well over 50 million people were affected throughout Ohio, Michigan, Pennsylvania, New York, Massachusetts, Connecticut and Vermont. The outage also spread into Ontario, Canada.

An estimated $10 billion economic loss was attributed to the blackout. While the vast majority of consumers had electricity restored within 48 hours, some parts of the United States did not have power for four days.

The 2003 blackout pushed reforms into “hyper-speed mode,” Lawson said. “Congress finally said, ‘We need something with teeth that’s mandatory and enforceable.’”

The ensuing Energy Policy Act of 2005 gave the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission authority over reliability. FERC chose NERC as the oversight organization, giving NERC, now called the North American Electric Reliability Corporation, new powers. In 2007, NERC’s 83 Reliability Standards were approved by FERC as the first set of legally enforceable standards for the U.S. bulk power system.

In collaboration with NERC, the power industry has adopted and implemented a preventative approach to maintain and improve bulk power system reliability. The idea is to aggressively go after the many small failures, such as maintenance issues, that can aggregate into larger problems.

Even though electricity is at our fingertips almost 100 percent of the time, getting it to our homes and workplaces from where it’s generated is a challenging process. Because large amounts of energy cannot be stored, electricity must be produced as it is used.

The grid must respond quickly to shifting demand and continuously generate and route electricity to where it’s needed the most. But significant changes and challenges are coming down the line. Issues affecting the grid include:

- Age. Parts of the electrical transmission facilities in the United States are many decades old. Given the age, some existing lines have to be replaced or upgraded and new lines may need to be constructed to maintain the electrical system’s overall reliability.

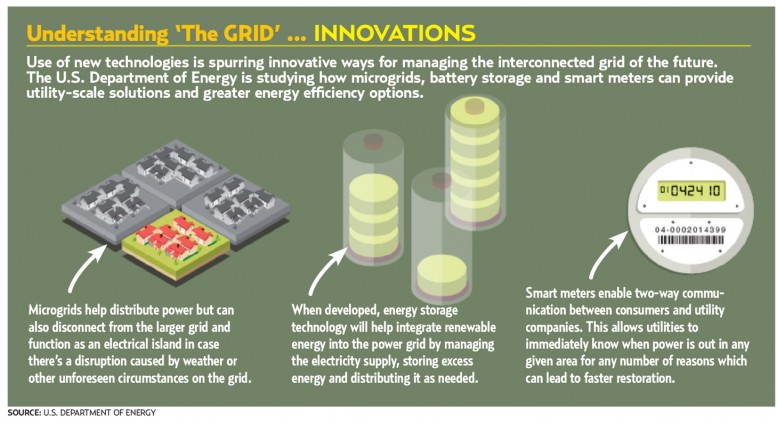

- New technology. Upgrades in technology now let consumers connect their own home-generated electricity to the grid — using solar panels or wind generators. The federal government is also investing in smart grid digital technology to more efficiently manage energy resources. The smart grid project also will extend the reach of the grid to access remote sources of renewable energy like geothermal power and wind farms.

- Cost. The smart grid and better reliability will not be free. According to a study done by the Electric Power Research Institute, creating a smart grid could cost up to $476 billion over the next 20 years. Utilities are likely to be stuck with a large chunk of the bill, which could impact consumers’ energy costs. But EPRI noted the country is likely to recoup those costs — and then some. The report said the smart grid could provide up to $2 trillion in benefits over a 20-year period, such as power reliability, integration of renewable energy, stronger cybersecurity and reduced electricity demand.

- Renewables. Federal climate change policy will rely on boosting energy efficiency and developing more sources of renewable energy. Both will impact the grid. Increasing transmission efficiency to better move and use electricity can potentially reduce the need for more generation and related transmission in the near future. Renewable energy resources will likely require construction of entirely new transmission lines. Wind, solar, geothermal, and other forms of renewable energy typically share a common setback: The areas where the power can be generated best are not population centers. For remote renewable facilities to be as beneficial as possible, associated transmission lines must also be built to move the power to where folks live. Renewables like wind and solar also present intermittency challenges for grid operators.

- Security. The grid may be vulnerable to both physical and cyber attacks. The cyber system is used to control the bulk power system and an attack can cause a blackout just as surely as if the transmission line was taken out of service.

One solution may be microgrids — localized grids that are normally connected to the more traditional electric grid but can disconnect to operate autonomously. Because they can operate independently of the grid during outages, microgrids could be typically used to provide reliable power during extreme weather events. (Please see sidebar on being prepared for power failures.)

Are these new challenges capable of creating a cascading blackout on the scale of the one in 2003 or 1965? “You can’t say it could never happen again. There are still things we haven’t planned for or have protections for, or are too costly to plan for,” Lawson said.

Utilities, agencies and regulators have worked hard to mitigate and eliminate such events and are cautiously optimistic. But fail-safe reliability may never be possible. Weather, the main cause of power outages, always remains a risk. And newer concerns like terrorist acts and cyber attacks have only added to the overall complexity and cost of keeping the power flowing.

This article and accompanying sidebars were compiled, written in most part, and edited by Richard G. Biever, senior editor of Electric Consumer. Contributions were edited from articles by the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association, U.S. Department of Energy, the U.S. Energy Information Administration. Other sources of information included Wikipedia, the American Public Power Association and NERC.