A crew from the Living Lands & Waters barge uses a smaller jon boat to gather trash and debris along the Ohio River banks. The crew takes the trash back to the main boat for it to be later recycled or disposed of properly.

Photo by April Corbin

It all comes down to the water.

Be it the biological essentials or the biblical allusions, something in our blood or in our souls draws us to it. All living things require it. And all that we put on the land, and even the land itself, eventually washes to it.

That’s the lesson seventh graders from Madison Junior High School took away from their visit to an ecology-focused barge that docked in their Ohio River town last fall. The Living Lands & Waters — a nonprofit environmental stewardship group — plies the Ohio and Mississippi rivers casting figurative and literal nets to remove trash and junk that have made their way into the water or onto the banks.

As the group travels, it brings students and community groups to the rivers to learn about ecological issues affecting water and land. Then it enlists their help in sweeping clean swaths of shoreline.

As the group travels, it brings students and community groups to the rivers to learn about ecological issues affecting water and land. Then it enlists their help in sweeping clean swaths of shoreline.

“Don’t we drink water from the river?” said Madison Ginn, one of the Madison seventh graders who heard the message. “Towns get their water from the river.”

There are so many places to properly put trash, but when people instead just dump it, she said, “It all leads down to the river. That’s like literally putting it into us.

“Don’t trash the water!” she implored.

Living Lands & Waters

Despite how vital our natural waterways are to the environment and economy, there are precious few organizations dedicated solely to cleaning them up. And there is only one that operates out of a barge that carries more than 100,000 pounds of debris.

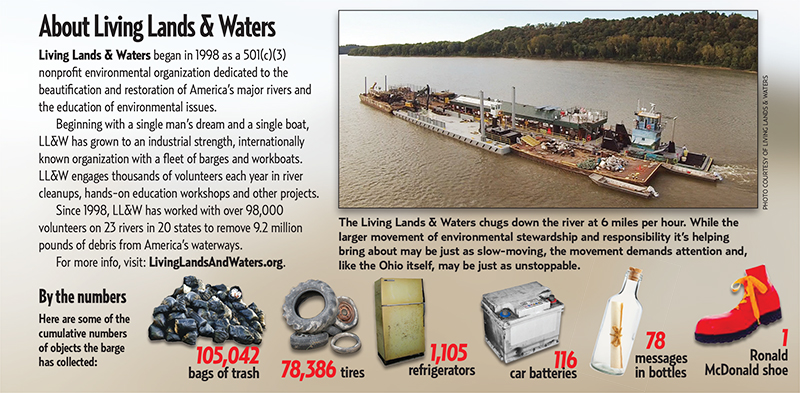

The Living Lands & Waters tug boat and barge travels the Ohio and Mississippi rivers with a crew that cleans the water and shorelines and educates school and other community groups about ecology. The group, based in East Moline, Illinois, made stops at river towns on both sides of the Ohio last fall and is scheduled to return to the Ohio River this fall.

Photo by Jolea Brown

Living Lands & Waters is considered the only “industrial strength” river cleanup organization of its kind in the world. Though officially based out of the Quad Cities along the Mississippi River in Illinois, the environmental nonprofit’s 10-member barge crew spends up to nine months of the year churning up and down rivers, docking at different cities.

Last fall, the crew stopped at various cities and parks on both the Indiana and Kentucky sides of the Ohio River. Among them were Patriot, Madison and Charlestown State Park where it hosted community cleanups and free student workshops, and inspired the next generation of environmental advocates. The barge is scheduled to return to Indiana cities this fall.

“I’ve been in the river before on a boat or a kayak, but it doesn’t ever look that dirty because I’m in the middle, and I don’t really see that much. But on the edge, there’s so much trash,” Madison said. “It just looked dirty getting closer to it.”

“For most people, trash along the river is out of sight, out of mind,” said Grace Waters, Living Lands & Waters’ development coordinator who writes grants for the organization while attending graduate school.

The barge forces people to confront the issue. It is a massive, mobile reminder of humankind’s impact on the Earth. In one corner: a mountain of tires. In another: a tangled mess of scrap metal and mariner’s rope. Nearby: a collection of steel drum containers, some of which once may have been filled with toxic chemicals.

Then, there is the chain link fence adorned with matted teddy bears, decapitated baby dolls, and other discarded toys. One part creepy, one part kitschy, finding items to affix to the fence is a point of pride for the crew.

“I thought it was pretty creepy area with all the dolls,” said Kenton Mahoney, the seventh grade science teacher at Madison Junior High. “They were all disfigured. The kids were super into it, trying to pick out a SpongeBob here or Tommy from Rugrats there. They were all about trying to find the toys they may have played with.”

“It was kind of like the stuffed animals off of Toy Story,” noted Noah Burkhardt, another of Mahoney’s students. All agreed: Sid — the mean kid who mistreated toys from the first Toy Story movie — had nothing on the people who lost or improperly dumped this poor river-ravaged collection.

Living lessons

Alexis Hunt, looks over what the seventh graders at Madison Junior High said was the “creepiest” part of the barge experience: a chain link fence decked with various disfigured dolls and stuffed toys pulled from the rivers.

When the barge docked in Madison, Mahoney said it came at the best of times for his students: “It fit perfectly with what we were doing then.” But it was also the worst of times: fall break at Madison Junior High hadn’t yet ended.

Mahoney encouraged students who stayed in town to take part for extra credit. Students in the Academy program, a cross-curricular program that takes real life experiences and situations and studies them across various disciplines, had just finished reading “A Long Walk to Water.” It’s a short novel, based on a true story, focusing on two children in African villages without access to clean, running water — thus the title. Students then studied the geography of Africa.

“In science, we were focusing on the whole water aspect — the environmental impact of waters, testing it,” Mahoney said. “We had gone down to our creek out here and tested that water. We were trying to make them see all these areas are interconnected.”

They also walked for a fundraiser to bring water to villages in El Salvador.

Five students showed up for the Living Lands & Waters visit. Mahoney was impressed with those that did make it to the riverfront that day. “The kids were really excited about it. Anytime kids are willing to give up a day of their fall break to do something like that is huge for them. I think they did gain a lot from it.”

He said they learned firsthand: “There is a lot of trash out there in the Ohio River, and we can do something to clean it up. What impacted them was seeing all the trash that was on the barge, seeing everything that had already been pulled out.”

“It really made a difference,” noted Stella Felts, also one of Mahoney’s students, “because it was fun to pick up trash — which was weird. Just doing that helped me realize that it was really important, and that if I do it more often, it would make our world to be a cleaner place.”

The free workshops bring teachers and students to the river to learn about the value of clean water, waste reduction, and the importance of recycling — using the work and operations of LL&W as a visible example of their importance. A representative from the local Jefferson County recycling center talked to the students that day, as well.

Students also could look at water samples under microscopes and other aspects of research. One demonstration included a tabletop diorama of a watershed that, using gelatin, shows what happens to certain pollutants when it rains and where it all goes.

“They had us look at how it ran down from the house and down the pipes down to the river. How it all led to the river and how it just made it disgusting,” said Stella.

“Once it gets in there,” added Madison, “you can’t take it out — unless you refill the entire river, and you can’t do that.”

Other Indiana schools visiting the barge included South Decatur Jr./Sr. High School, Father Michael Shawe Memorial Jr./Sr. High School from Madison, Our Lady of Providence Jr./Sr. High School from Clarksville, Franklin County High School, Switzerland County High School, Henryville Jr./Sr. High School, Rock Creek Community Academy from Sellersburg, New Washington Middle/High School and Seymour High School.

Since it was founded in 1998, LL&W has removed approximately 9.2 million pounds of debris from 23 waterways in 20 states. Crew members have taught countless educational workshops and gotten support from more than 98,000 volunteers.

The majority of what they recover gets recycled. The rest is disposed of properly. In some instances, though, cleanups uncovered items too dangerous for Living Lands to handle — like meth labs, barrels filled with toxic chemicals, or illegal dump sites containing too much for even the barge to take on. In those cases, the group must call experts equipped to handle the unique circumstances.

Making a difference

Tammy Becker has been with Living Lands since 2002 and is married to its founder, Chad Pregracke. She said the most frequent reaction is shock when people see the barge before a community cleanup and then afterward.

“People are, like, all that came from right here? It’s eye-opening.”

The good news is that Pregracke and his crew believe conditions are getting better.

“Back in 2001 or 2002, people couldn’t understand why we were doing this work,” said Pregracke. “Now people are saying, ‘It’s about time!’ It’s taken years and years, but it’s a huge change. People have brought more attention to the issue. The mentality is changing.”

Development Coordinator Waters adds that the re-education process emphasizing not littering and not dumping into the watershed can be especially tough in areas where environmentalism and conservation are sometimes seen as superficial progressive causes.

“You just have to keep stating the facts,” she said.

Like the fact that chemicals from just one cigarette butt can contaminate 2 gallons of water. “People just don’t know,” said Ashley Stover, a former crew member who spent five years on the barge. “There are people who don’t know they get their drinking water from the river. That’s why we do workshops and cleanups. To go, ‘This is why you don’t throw your stuff into the river.’”

Just to answer Madison’s earlier rhetorical question and reiterate Stover’s comment: Yes, some 5 million people rely on the Ohio River for their drinking water.

Leaving the world a better place for future generations is the common thread among all of the people who rotate through the barge as crew members. It’s how they get through the tight quarters, long hours, and unpredictable demands of the job.

“Everyone here has the same goal,” said Waters. “It’s to make a difference in the world.”

That was one of the takeaways left with the visiting students.

“I like being outside, and I like being by the water. And anything to help the water feels good to do,” said Madison. “I live in a country area, but we have creeks. So I connected to the river.”

Madison said in summer she likes to swim and fish in the creeks and look for crawfish and tiny shells. And even in her rural streams she sees discarded fish hooks, glass and plastic bottles.

“People don’t realize how much they throw in there. They throw a little plastic bottle down there, and that plastic bottle turns into a lot of little pieces,” she explained. “And the fish can eat those pieces, and it can poison the fish, and then the fish can poison us. It all leads to something really bad.”

This story was revised from an article written by April Corbin, a freelance writer from Henderson, Nevada, and added to by Richard G. Biever, senior editor of Electric Consumer. Corbin’s article previously appeared in Kentucky Living, the electric co-op publication of the Bluegrass state. For more information, visit LivingLandAndWaters.org.