For Eileen Baker-Wall, the Levi and Catharine Coffin house is more than just a state historic site and national landmark. It’s also something as deeply personal and cherished as her family’s rarest heirloom.

In the dining room of the Levi and Catharine Coffin house, Eileen Baker-Wall holds wooden shoes that belonged to her great-great grandfather William Bush, a slave who found freedom with the help of the Coffins on the Underground Railroad. Baker-Wall, a retired educator, volunteers as a tour guide for the historic site.

Her great-great grandfather William Bush perhaps owed his life to the Coffins, their home and the Wayne County community of Newport. Perhaps Baker-Wall herself would not be here if not for the freedom Bush found there 175 years ago.

As a fugitive slave on the run in North Carolina, Bush had himself shipped in a wooden box to: “Newport, Wayne County, Indiana; Care of Levi Coffin.” That’s how one of several stories of his escape from bondage goes.

But one way or another, Bush came to Newport (now called Fountain City) sometime in the 1840s. He found freedom and safety there. So much so that Bush decided to stay in Newport, unlike the thousands of other freedom-seeking slaves who struggled on to Canada. Across the border in what became Ontario, they would be free of federal fugitive slave laws and not have to be looking over their shoulders.

“The U.S. 27 corridor — there are so many pieces of evidence of people following that corridor up to Fort Wayne, farther on into Michigan and into Canada,” said Baker-Wall. “As long as he felt safe, where he was protected by the people and useful to the people, he was welcomed to the community.”

Even then, the Coffins’ home was known as the “Grand Central Station of the Underground Railroad.” The “Railroad” was a secretive, loose network of whites and free blacks who aided, hid and helped ferry runaway slaves to freedom in the North before the Civil War and the abolition of slavery in the United States.

Bush made a new life for himself in Indiana. He became a successful blacksmith and also a lay veterinarian, two skills needed for any community back then. He married, began a family, was widowed, remarried and had more children.

In spite of frequent slave hunters passing through town and federal fugitive slave laws that required folks even in the North to turn in suspected runaways, Bush helped other freedom seekers on their journeys. “He must have felt a great deal of comfort there,” Baker-Wall added. “He was a good citizen.”

Baker-Wall said that from what she’s been able to piece together from written records and family history whispered from one generation to the next, she believes Bush’s first wife may have died giving birth to Baker-Wall’s great grandmother around 1864.

William Bush is buried at Fountain City’s Willow Grove Cemetery. Bush, who escaped slavery in the South with the assistance of Levi and Catharine Coffin and others along the Underground Railroad, found safety and a permanent home in the town in the 1840s. He then assisted others fleeing bondage on the Underground Railroad. He died in 1898. Five generations of his direct descendants lived in Fountain City.

Photo by Richard G. Biever

As a volunteer tour guide at the Levi and Catharine Coffin State Historic Site, the 73-year-old retired educator from Richmond said she loves to tell school kids of her bond to the Coffins and one of the slaves they helped.

“Some will gasp. One asked for an autograph. There is awe because there’s a connection,” she said. “It’s been a remarkable experience to give them that connection because that makes it real.”

She says she tells the groups, “You’re standing on the same floor the Coffins stood on, the same floor slaves walked on. Here we are, … all these years later.”

While Baker-Wall’s connections to the home and its past are as real and as close as the last breath she’s taken, so much of the history of Bush and the Coffin house are just as untouchable. By its secretive and loose nature, so much of the Underground Railroad has been lost to time. In the black communities, especially, stories were passed by oral tradition. Little was written and saved.

Baker-Wall noted that even within her own family, little was said of slavery and the past. Her father, Bush’s great grandson, was a bit more open than her mother. But she said she didn’t learn of Bush and the family’s connection to the Coffin house until she started asking questions in high school — even though she was the fifth generation of Bush’s family growing up right there in Fountain City.

The Coffin house is perhaps the country’s best known “station” on the Underground Railroad. Yet, there’s still so much to know about it, too. Though Levi Coffin published his memoir in 1876, a year before his death, he purposely kept some details vague and wrote little about the house that became the historic site. He kept diaries of his days in Indiana, but those volumes have never been found.

“If these walls could talk … we could have all those pieces of history we don’t have,” said Baker-Wall. She’s on a mission to uncover and document as much as she can about her family and the Coffin house.

“It’s something that I didn’t know as a child,” she said. “That my people helped our people get to freedom … it feels very, very good.”

She said the positive lessons the historic site exemplifies of interracial cooperation and equality are still just as important today. “Whenever we can come and say this is how we lived together in the course of history — despite things like the Ku Klux Klan.…

“Human beings should be treated according to God’s law. This is how people work together and live together.”

Richard G. Biever is senior editor of Electric Consumer.

After a cold winter’s night on the run, a family of slaves escaping from the South finds safety and shelter at the home of Levi and Catharine Coffin, depicted in this 1893 painting, “The Underground Railroad,” by Charles T. Webber. The Coffins opened their home in Newport (now Fountain City), Indiana, from the mid-1820s to 1847, as a station in the secretive network that aided the freedom seekers in their flights before slavery was abolished in the United States. This oil on canvas is in the collection and on exhibit at the Cincinnati Art Museum. The Coffins moved to Cincinnati in the spring of 1847 and continued to work with the Underground Railroad there.

New light on the Underground Railroad

$3.8 million Interpretive Center opens beside Levi and Catharine Coffin house

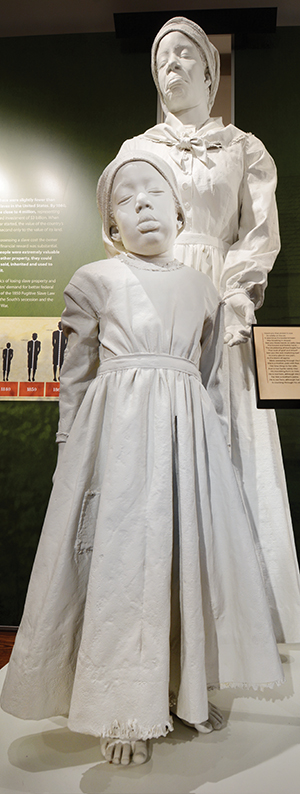

Among its many horrors, slavery ripped families apart. A mother’s farewell to her daughter is depicted in this gripping sculpture displayed at the new Coffin Interpretive Center.

The true story of a slave fleeing Kentucky in winter on ice floes over the Ohio River with her child in her arms, rather than see the child sold away, became a chapter in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.” The woman, given the name Eliza Harris by Catharine Coffin, passed through the Coffin home with her child on their way to Canada. Catharine was known as “Aunt Katy” to the freedom seekers she welcomed in her home.

The Coffins appear as Simeon and Rachel Halladay in the 1852 Stowe novel that stirred growing anti-slavery sentiments in the North.

The story of how Levi and Catharine Coffin helped African-American slaves reach freedom in the decades before the Civil War has been told at their former house in Fountain City almost from the time it was built in 1839. So many slaves successfully passed through the Federal-style brick home, it became known as the “Grand Central Station of the Underground Railroad.”

After the house was saved by the town’s residents from demolition in the 1960s and it became a state historic site, an association of dedicated volunteers researched, restored, opened up and maintained the two-story house. Over the past 50 years, it became one of Indiana’s best-known historic sites. It is also a National Historic Landmark.

This past December, just as Indiana celebrated its bicentennial, a new chapter was opened in the mysterious tale of the Underground Railroad in Indiana. The Indiana State Museum and Historic Sites, in conjunction with the Levi Coffin House Association, its long-time caretaker, cut the ribbon on a new state-of-the-art Interpretive Center beside the historic house.

“The new center symbolizes and celebrates the spirit and enduring courage of freedom seekers — escaped slaves — and 19th-century anti-slavery activists Levi and Catharine Coffin, as well as their home, which serves as one of the best-documented and important Underground Railroad sites in the United States,” said Joanna Hahn, the site’s manager. “The site saw more than 1,000 freedom seekers pass through en route to freedom.”

Even before opening, the center was named one of the 12 best new museums to visit in 2016 by Smithsonian Magazine.

The center had been on the drawing board since 1999. In 2004, Whitewater Valley REMC consumers provided $2,000 toward matching federal grant fundraising efforts for the center through the REMC’s Operation Round Up program.

The front façade and sides of the new $3.8 million facility were designed to replicate the original 1837 building that stood on the corner adjacent to the house. Though that original structure couldn’t be saved, flooring, windows and other features were salvaged and reused in the new structure. Wooden beams were reclaimed for benches for theater seating and other uses in the center.

The center features the exhibition “Souls Seeking Safety: Bringing Indiana’s Underground Railroad Experience to Life.” The exhibit puts the work of the Coffins and others in national context and shares the voices and experiences of the freedom seekers.

It also explains how individuals battled the economics that supported slavery through the “Free Labor” movement, a precursor for today’s Fair Trade efforts. Levi, a successful merchant and businessman, began selling only items made without the use of slave labor in his general store.

Another change: the entire historic site was renamed as The Levi and Catharine Coffin State Historic Site — to honor the work of both husband and wife who dedicated their lives to eradicating slavery and inequality.

“Visitors now have the opportunity to explore more fully what Levi Coffin called the ‘Mysterious Road,’” said Susannah Koerber, senior vice president of collections and interpretation at the state museum and historic sites.

The Levi and Catharine Coffin State Historic Site, right on U.S. 27 in Fountain City, now includes the original Coffin house, on the right, and the new Interpretive Center, left.

The historic Coffin home

While the Interpretive Center provides a bigger picture of the Underground Railroad and slavery and allows for more detailed impressions, the Coffin house remains the focal point of the historic site.

From the outside, the house looks like any that a successful Quaker might have built in 1839. On the inside, however, it has some unusual features for Hoosier homes of the day, causing speculation. Did the Coffins add these for the security and convenience of their Underground Railroad passengers? (Please see photos below.)

The Coffins

The Coffins came to Fountain City (then called Newport) from North Carolina in 1826 in a migration of Quakers morally opposed to slavery. While not planned, they settled on what turned out to be the crossroads of three Underground Railroad routes North. Almost immediately, the Coffins began aiding freedom seekers.

In Newport, the Coffins were surrounded by like-minded Quakers, and the entire community acted as lookouts when slave hunters came into town. Though aiding fugitive slaves broke federal laws, Levi in his memoirs spoke of higher laws, God’s laws.

Unlike most in the Underground Railroad, Coffin was not coy about his efforts. While this made him a subject of surveillance and put him in danger, Coffin knew the law and always demanded a warrant before allowing hunters into his home or to search his wagons. Though there were close calls, it’s believed his home was never subjected to a search.

In 1847, the Coffins moved to Cincinnati where Levi began operating a wholesale warehouse to supply goods to the expanding free-labor stores. The Coffins continued working with the Underground Railroad there.

They intended to return to their home in Newport and rented it out. But after the Civil War, they stayed in Cincinnati and sold the house in 1867. Levi died in 1877, and Catharine died in 1881. Both are buried in Cincinnati.

Over the next 100 years, the house passed through several owners and, in the early 1900s, was even used as a boarding house. After the state purchased the house in 1967, the Levi Coffin House Association raised funds to restore it as close as possible to its 1839 condition.

Hahn noted that now, under full state oversight and operation, the Coffin historic site will have access to more resources for continued research and further restoration.

Source: Indiana State Museum and Historic Sites

In 1839, the Coffins built the home that, purposefully or not, was ideal for hiding runaway slaves. “Guests” entered through the kitchen or a cellar door. Unusual for Indiana homes at the time, the cellar had a fireplace and a brick floor (above).

An upstairs bedroom had a sloping long, narrow closet that could hide a dozen people, but access was through a small door which could be easily hidden by a bed’s headboard.

A spring-fed well in the cellar was another unusual feature. It allowed the Coffins to conceal the amount of water the household used, which kept from tipping off the number of people inside, in case slave hunters were surveilling the house.

If you go:

Levi and Catharine Coffin State Historic Site

201 U.S. 27 North, Fountain City, IN 47341

Parking is available in a lot between the Interpretive Center and the Coffin House. Street parking is also available.

What you’ll see and learn:

- Interpretive Center — Opened in December 2016, the $3.8 million center is next door to the original Coffin home. The Smithsonian Magazine listed the center as one of the top 12 new museums to visit in 2016.

Includes a short introductory film about the Coffins and the exhibit “Souls Seeking Safety,” which was designed for visitors to explore on their own and form their own impressions. Gallery hosts are available to answer questions.

The Interpretive Center visit averages about 30 minutes, but visitors are welcome to stay as long as they like to reflect. - Levi and Catharine Coffin Home — Federal-style brick home built in 1839 is the third and final home owned by the Coffins in Newport (later named Fountain City). The guided tour brings rich context to the historic home through the stories Levi Coffin shared in his memoir and tells how the home was used to harbor freedom seekers. The home became a state historic site in 1966 and is a National Historic Landmark. The home tour includes the barn out back. The barn features a period buggy and a false-bottom flatbed wagon (the kind that Coffin used to hide freedom seekers when ferrying them to the next Underground Railroad stop north). The home and barn tour lasts about an hour.

- Interpretive Center Gift Shop — Unique Indiana-related items, including food, jewelry and décor, and an expanding book selection pertaining to the Coffins, the Underground Railroad and Indiana history are available in this main-floor shop.

Admission (includes Interpretive Center and tour of home):

- Adults — $10

- Seniors (ages 60 and older) — $8

- Children (ages 3-17) — $5; under 3 years old — free

- ($1 discount given for groups of 15 or more; see student info below)

Hours (with the new center, the site is now open year-round):

- Tue-Sat — 10am-5pm (last tour of home begins at 4pm)

- Sun — 1-5pm (beginning in February)

- Closed — Mondays and various holidays

School Groups and Tours:

Student groups can visit for free. Academic topics cover slavery, abolitionism in the U.S., free black communities, Quaker history and the Underground Railroad, freedom seekers and slave hunters. Visit includes self-guided tour of Interpretive Center and a guided tour of the Coffin home. Call the number below to schedule visit.

Contact Info:

- Phone: 765-847-2432

- Email: LeviCoffinCenter@IndianaMuseum.org

- Website: IndianaMuseum.org/levi-and-catharine-coffin-state-historic-site

Indiana: Crossroads of Freedom

The Ohio River separated the free states of Indiana, Illinois and Ohio from Kentucky where slavery was legal. While three major Underground Railroad routes through Indiana were identified in the late 1800s, ongoing research revealed many more routes that were more like a spiderweb.

The Underground Railroad was not a physical road, secret tunnels or passageways. Rather, it was a secretive network of people who aided freedom-seeking slaves in their flight northward across the Ohio and into Canada.

Some UGRR conductors, like the Coffins, were well-known Quakers and abolitionists who were part of a trusted, word-of-mouth network. They sheltered runaways for short or extended periods of time until the threat of slave catchers had passed and it was safe to ferry them to the next station. Others were spur-of-the moment participants who rendered assistance when chancing upon a runaway or group on the run.

Research has revealed examples of the UGRR operating in all 92 Indiana counties before the abolition of slavery following the Civil War.

For more information

Here are some websites to check out to learn more about the Underground Railroad:

Elijah Anderson Home: http://www.in.gov/dnr/historic/2798.htm

Hoosier National Forest and the Lick Creek settlement: https://www.fs.usda.gov/recarea/hoosier/recarea/?recid=81892

Indiana Freedom Trails: http://www.indianafreedomtrails.org

Indiana History Bureau: www.in.gov/history/2589.htm

National Parks Service Network to Freedom: www.nps.gov/subjects/ugrr

National Underground Railroad Freedom Center:

50 E. Freedom Way, Cincinnati, OH 45202

freedomcenter.org

Ohio River National Freedom Corridor: www.OhioRiverNationalFreedomCorridor.org

Speed Cabin (Montgomery County Historical Society): www.lane-mchs.org/page10

The Underground Railroad in Indiana: http://visions.indstate.edu/civilwar/railroad.html

Revisit an article on the Lick Creek Settlement in Orange County, Indiana, from the February 2002 issue of Electric Consumer.

Revisit an article on the Lick Creek Settlement in Orange County, Indiana, from the February 2002 issue of Electric Consumer.